A tour through the literature

I first got to know the park in the 1950's, when I was

living near Baker Street with my sister. It became a favourite place for

both us. Coming across a description in a book or a poem – seeing

how someone else had perceived it – was always rewarding, and I'd

copy out anything that particularly appealed to me.

After my sister's death I decided to write a commemorative essay, in the

form of a walk around the park visiting some of the spots our favourite

authors had described. It was only intended for family and friends, but

when I was assembling material for these pages I thought that a shortened

version might be of interest to others too.

Bear in mind that it was written in 1992 and some aspects of the park have changed since then, as will be apparent from my photos (note: click on an image for a more detailed view). If you are interested in an up-to-date walk, without the literary bits, you can't do better than visit 'a walk from Clarence Gate and onwards', where there are several laid out for you, handsomely illustrated.

The tour

No writer has evoked Regent's Park more frequently, more perceptively, or more lovingly than Elizabeth Bowen. Her two best-known novels both open with a chapter set entirely within the Outer Circle, and it provides the background for several short stories.

'I

had always placed this park among the most civilized scenes on earth',

she wrote, in an essay, London 1940. She was an air raid warden

at the time and living at 2 Clarence Terrace, near the Baker Street corner

of the park, her home for sixteen years. 'The Nash terraces look as brittle

as sugar – actually, which is wonderful, they have not cracked; though

several of the terraces are gutted'. But successive bomb blasts were to

weaken Clarence Terrace beyond restoration, and the building we see now

is a 1960's replica of the original Decimus Burton facade (right).

'I

had always placed this park among the most civilized scenes on earth',

she wrote, in an essay, London 1940. She was an air raid warden

at the time and living at 2 Clarence Terrace, near the Baker Street corner

of the park, her home for sixteen years. 'The Nash terraces look as brittle

as sugar – actually, which is wonderful, they have not cracked; though

several of the terraces are gutted'. But successive bomb blasts were to

weaken Clarence Terrace beyond restoration, and the building we see now

is a 1960's replica of the original Decimus Burton facade (right).

The Death of the Heart (1938) begins with two people walking around the Boating Lake.

'That

morning's ice, no more than a brittle film, had now cracked and was floating

in segments...On a footbridge between an island and the mainland a man

and woman stood talking.' The bridge is probably the one by the Boat Shed,

and it is here we start our tour, but as it makes a rather dull photo

I've chosen another view of the same area (left). We follow Anna and St

Quentin around the lake to Clarence Gate.

'That

morning's ice, no more than a brittle film, had now cracked and was floating

in segments...On a footbridge between an island and the mainland a man

and woman stood talking.' The bridge is probably the one by the Boat Shed,

and it is here we start our tour, but as it makes a rather dull photo

I've chosen another view of the same area (left). We follow Anna and St

Quentin around the lake to Clarence Gate.

'Beside the criss-cross diagonal iron bridge, three poplars stood up like frozen brooms... The swans, the rims of ice, the pallid withdrawn Regency terraces had an unnatural burnish, as though cold were light...St Quentin threw a homesick glance up at Anna's drawing room window' (right).

The three poplars have gone, but otherwise it seems to be much the same today. Anna's house figures extensively throughout the book. It's given a fictional address but is generally agreed to be an exact description of the author's own house. She seems to have been fond of the poplars. They appear again in a short story about a weepy small boy and his awful mother, Tears, Idle Tears (1941); but now it is May and they have become 'delicate green brooms' instead of frozen ones.

Another short story gives a clue to their demise. I Hear You Say So concerns the unsettling effects of the first nightingale, in the week after the war in Europe ended. 'Just inside the park three poplars, blasted the summer before by a flying bomb, stretched the uncertain leaves they had put out this year towards those of the unhurt trees.'

This same corner of the park is depicted in a more sinister light in Patrick Hamilton's trilogy, Twenty Thousand Streets Under The Sky (1934). It has often been said that these 424 acres resemble the parkland of a stately home, rather than a recreation ground for city dwellers. This would have struck a chord with Bowen. She had inherited her family's estate in Ireland; and her fictional couple, well-to-do sophisticates, share something of their creator's proprietorial concern for the land. Hamilton and his characters, a much put-upon barmaid and her grotesque, ageing suitor, occupy a very different world.

'They were walking briskly now by the lake in the direction of Clarence Gate, whence they were to emerge for their supper into London, whose lights were now seen glittering, and whose buses and trains could be heard roaring, an entirely furious and disparaging welcome to the surface to divers in its dark parks' (left).

Here the park seems to reflect Hamilton's own darkness of the soul; a biographer described him as 'one of the chronically dissolute and distressed who wander the dingy London streets and find refuge in its pubs.' Perhaps it was the hangovers that gave him such a sour view of things. In another chapter the same couple

'had entered the park at York Gate, and were walking up the main avenue towards the Zoo amidst the winter-gripped flowerbeds and the rippling murmur of a post-prandial Sunday crowd gratefully disporting its undistinguished self in the sun.'

We have reached the Broad Walk via the footpath beside the Outer Circle. Now we head north towards the Zoo, but turn left at Chester Road and enter Queen Mary's Rose Garden. It provides the title for a poem that Sylvia Plath wrote about 'this wonderland / hedged in and evidently inviolate', in 1960, when she was living in Chalcot Square, Primrose Hill. She must have been a frequent visitor to the park, particularly after her first child was born in April. The poem will never rank as one of her greatest, but it wins a place on our tour for the wry affection it shows. The first of four verses goes:

'In this day before the day nobody is about.

A sea of dreams washes the edge of my green island

In the centre of the garden named after Queen Mary.

The great roses, many of them scentless,

Rule their beds like beheaded and resurrected and all silent royalty,

The only fare on my bare breakfast plate...' (right).

It turns out that this is a 6am visit, with 'no walker and looker but myself.' Baby isn't mentioned, but one wonders whether an outing at this time of day resulted from the disturbed routines of pregnancy and motherhood. Another poem, Morning Song, describes an early morning feed while 'the window square / whitens and swallows its dull stars.'

We return to the Broad Walk, the setting for several scenes in Virginia Woolf's novel, Mrs. Dalloway (1925).

'The long slope of the park dipped like a length of green stuff with a ceiling cloth of blue and pink smoke high above, and there was a rampart of far, irregular houses, hazed in smoke, the traffic hummed in a circle, and on the right, dun-coloured animals stretched long necks over the Zoo palings, barking, howling. There they sat down under a tree.'

My limitations as a photographer will be evident here, but I am pretty sure the viewpoint is right. Clean Air regulations have banished the smoke, and the dipping slope would have been more apparent before layers of bomb damage rubble from World War Two were spread over the playing fields (above).

The couple who sit down and survey this scene are a shell-shocked ex-soldier and his Italian wife. The doctor has assured her that Septimus 'had nothing whatever seriously the matter with him but was a little out of sorts.' The man later commits suicide, as his author was to do, and in these pages Virginia Woolf expresses the anger she felt at the way her own bouts of insanity were treated. The wife, Rezia, is in despair:

'I am alone: I am alone! she cried by the fountain in Regent's Park (staring at the Indian and his cross), as perhaps at midnight, when all boundaries are lost, the country reverts to its ancient shape...such was her darkness.'

The fountain has been rather knocked about since then, and the water cut off, but the eroded features of Sir Cowasjee Jehangir, wealthy Parsee gentleman, are just about discernible (right). The inscription tells us that it was a gift to the people of England in gratitude for the protection enjoyed by Parsees under the British Rule in India. That was in 1869. Some forty years later Virginia, wearing a turban and moustache not unlike Sir Cowasjees's, went aboard the flagship of the Home Fleet pretending to be an Abyssinian prince in the retinue of an equally bogus Emperor. They were received by the Admiral and given a tour of inspection with full naval honours. It became known as 'The Dreadnought Hoax'; there was a great row about it and questions were asked in Parliament.

For another character in the novel, a stroll in the Broad Walk awakens childhood memories:

'Yes, he remembered Regent's Park; the long straight walk; the little house where one bought air-balls to the left; an absurd statue with an inscription somewhere or other.'

The air-balls – toy balloons – have gone, but the absurd statue is probably the Indian fountain. The author's memories of it would have dated back to the period fifteen years earlier when she lived in nearby Fitzroy Square. On the morning of Christmas Eve 1909 she was walking alone in the park when she suddenly decided to go to Cornwall. It was 12.30pm and the train left at 1. She returned home, packed a bag and got to Paddington in time to catch it: try doing that today!

A few yards on from the Indian fountain we come to the Zoo. I'm excluding it from our tour because writers tend to use it as a metaphor in itself, without reference to the surrounding parkland. Ted Hughes is an exception in this respect; the title poem of his 1989 volume, Wolfwatching, firmly relates the animals to the world outside. The wolf enclosure is beside the Broad Walk: they can see passers-by in the park, cycling or walking their dogs. The poem begins:

'Woolly-bear white, the old wolf

Is listening to London. His eyes, withered in

Under the white wool, black peepers...'

He is contrasted with a young wolf, with

'Asiatic eyes, the gunsights

Aligned effortless in the beam of his power.

...He's waiting

For the chance to live, then he'll be off.

Meanwhile the fence, and the shadow-flutter

Of moving people, and the roller-coaster

Roar of London surrounding, are temporary...'

At

the end of the Broad Walk we cross the Outer Circle to a canal bridge,

scene of a tragic and disturbing incident described by Charles

Dickens in The Uncommercial Traveller. It's not far

from the main entrance to the Zoo, depicted in a contemporary engraving

on the left. One afternoon in the winter of 1861,

At

the end of the Broad Walk we cross the Outer Circle to a canal bridge,

scene of a tragic and disturbing incident described by Charles

Dickens in The Uncommercial Traveller. It's not far

from the main entrance to the Zoo, depicted in a contemporary engraving

on the left. One afternoon in the winter of 1861,

'I was walking in from the country on the northern side of the Regent's Park – hard frozen and deserted – when I saw an empty Hansom cab drive up to the lodge at Gloucester-gate, and the driver with great agitation call to the man there'.

Dickens runs after the cab, which stops at a bridge 'near the cross-path to Chalk Farm'. The body of a drowned woman is on the towpath, broken ice and puddles of water 'dabbled all about her...The dark hair streamed over the ground.'

'A barge came up, breaking the floating ice and the silence, and a woman steered it. The man with the horse that towed it, cared so little for the body, that the stumbling hoofs had been among the hair, and the tow-rope had caught and turned the head, before our cry of horror took him to the bridle. At which sound the steering woman looked up at us on the bridge, with contempt unutterable, and then looking down at the body with a similar expression – as if it were made in another likeness from herself...steered a spurning streak of mud at it, and passed on.'

The bargees' behaviour suggests that canal drownings were not a rarity in those days. Another unpleasant feature of the park, 'ruffianism', had upset Dickens some twenty years earlier. Recalling this in The Uncommercial Traveller he says,

'The blaring use of the very worst language possible, in our public thoroughfares – especially in those set apart for recreation – is another disgrace to us...Years ago, when I had a near interest in certain children who were sent with their nurses, for air and exercise, into the Regent's Park, I found this evil to be so abhorrent and horrible there, that I called public attention to it...'

At that time he was living at 1 Devonshire Terrace (now the corner of Marylebone High Street and Marylebone Road), and according to another writer the 'near interest' refers to Dickens's own family: 'his nurse and children were insulted and molested by tramping women and girls.' Nowadays one is unlikely to encounter anything worse than the occasional alcoholic dosser.

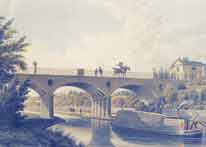

We

are still at St. Mark's Bridge, and can now descend to the towpath and

walk westward along the canal, coming up again at Primrose Hill Bridge.

Pause here to look right towards the next bridge, Macclesfield, popularly

known as Blow-up Bridge. A decade after the canal drowning that Dickens

witnessed this was the scene of a tragedy on a larger scale. 'The sleep

was broken by one of the most terrible explosions of gunpowder, powerful

enough to throw down masses of stone', in the words of a local resident,

Giuseppe Campanella. In An

Italian on Primrose Hill (1875) he describes the night in October

1874 when a barge laden with gunpowder blew up, killing the crew of three.

The bridge was rebuilt as a replica of the first one, depicted (above)

by T.H. Shepherd c.1828.

We

are still at St. Mark's Bridge, and can now descend to the towpath and

walk westward along the canal, coming up again at Primrose Hill Bridge.

Pause here to look right towards the next bridge, Macclesfield, popularly

known as Blow-up Bridge. A decade after the canal drowning that Dickens

witnessed this was the scene of a tragedy on a larger scale. 'The sleep

was broken by one of the most terrible explosions of gunpowder, powerful

enough to throw down masses of stone', in the words of a local resident,

Giuseppe Campanella. In An

Italian on Primrose Hill (1875) he describes the night in October

1874 when a barge laden with gunpowder blew up, killing the crew of three.

The bridge was rebuilt as a replica of the first one, depicted (above)

by T.H. Shepherd c.1828.

From the Outer Circle we head south across the long slope and over a bridge. A short walk along the Inner Circle brings us to the Rose Garden restaurant, scene of a farcical encounter related by John Mortimer in his autobiography, Clinging to the Wreckage (1982). He is very vague about dates but it must have been some time in the Sixties when he arranged to meet his wife, the novelist Penelope Mortimer, to discuss their divorce.

'We sat in the sunshine and Penelope ordered spare-ribs. It was extraordinarily peaceful as we sat surrounded by a silence which was only emphasized by the distant murmur of traffic.'

Suddenly Penelope freezes, looks horrified, sweeps up her belongings and rushes off. Mortimer sits on, musing at this turn of events, and absent-mindedly bites into the half-eaten spare-rib. Unfortunately he has had a tooth capped that morning, and part of the cap breaks off. At that moment he is called to the phone. It's Penelope, apologising.

'I said that I understood perfectly and that it was not an easy thing for anyone to sit at lunch discussing a divorce. It wasn't exactly that, she explained. What had happened was that, as she bit into her spare-rib, a cap came off her tooth and she hadn't wanted to go on sitting with a mouthful of gap...

I went out into the sunshine where the plates hadn't yet been cleared away. And there was the spare-rib which had captured fragments of dentistry from each of us, and which held them tightly and remorselessly together.'

And here we end our tour.